The history of the RHS Chelsea Flower Show

With the RHS Chelsea Flower Show returning in May, we get back into the Chelsea mood with our take on the highs (and occasional lows) of Chelsea Flower Show. Words Ambra Edwards

On 20 May 1913, the Royal Horticultural Society held its Great Spring Show in the grounds of Chelsea Hospital for the very first time. It was a roaring success. So many exhibitors applied to join the show that only half could be accommodated, but of the 244 who made the cut, Kelways, Blackmore & Langdon and McBeans Orchids are still exhibiting over a century later.

The show, pronounced the Gardeners’ Chronicle on 29 May, ‘exceeded all expectations’, ‘so large and numerous were the groups, and so magnificent the quality of the varied exhibits’. A massive single tent extended over two acres, enclosing 84 ‘large groups of flowers, plants and shrubs’ and 95 exhibition tables.

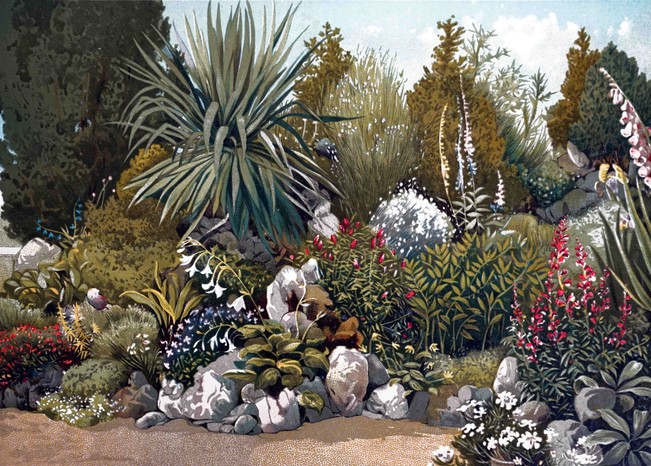

Out in the open, there was a chance to indulge the huge popular appetite for rock gardening. The first Gold Medal for a garden went to J Wood of Boston Spa, with a rocky scene that might ‘easily be imagined to be a bit of the Yorkshire Fells bodily transported South’.

The Society’s experience of shows had not always been so glorious. Its first exhibit appears to have been a potato, proudly displayed by a Mr Minier in 1805. There was no thought of involving the public until 1827, when the Council, desperate for cash (the Secretary having embezzled the funds and hot-footed it to France), decided to hold a fête at the Society’s garden in Chiswick.

It proved such a money-spinner that it was repeated the following year, despite fears of the ‘dissipation’ such merrymaking might engender among gardeners. In 1829, however, disaster struck, in the form of torrential rain. Visitors, it was reported, stood ‘ankle deep in water oozing from the gravel; shrieks were dreadful and the loss of shoes particularly annoying.’ This experience, of course, is perfectly familiar from subsequent Chelseas, including 1971 and 1995.

More sober shows continued to be held at Chiswick over the next two decades, but petered out in 1857, as the Society ran out of money. But it was during this time that a non-competitive system of medals was introduced very similar to that employed today. A great new garden at Kensington, backed by Prince Albert, and intended as a more accessible show venue, hosted the first Great Spring Show in 1862, but proved a financial disaster. In 1888, Kensington was abandoned, and the Show moved to Inner Temple. The Benchers, however, became increasingly disenchanted with the noisy and malodorous proceedings, and by 1911, the RHS was looking round for another site.

More like this

Tea in a tent

In 1912 there was no show at all, as the RHS lent its support to an international horticultural extravaganza staged in the grounds of Chelsea Hospital. This, however, served to demonstrate the suitability of the site on the Chelsea Embankment, with its easy access and commodious lawns.

Though the RHS leased only ten acres (the 1912 exhibition took 28), there was still room for 17 outdoor show gardens. The Royal Artillery Band provided music. Tea could be taken in the tent for 1 shilling or on the lawn for 1/3d (there was also an area labelled ‘Second Class Refreshments’). There was royalty in the shape of Princess Alexandra and horticultural royalty in Waterers of Bagshot, tree supremo RC Notcutt and Allwood Carnations. All the key Chelsea ingredients were in place.

Showing item 1 of 7

A second successful show was staged the following May, but in August, war was declared. 1915 and 1916 saw low-key shows, but no more followed for the remainder of the war. When Chelsea resumed in May 1919, the gardening landscape had changed beyond all recognition. Yet the aristos still turned up on the first day to tour the show with their head gardeners. The Hon Vicary Gibbs, or rather his gardener Edwin Beckett, continued to sweep the board with his mammoth vegetables right up until 1930.

Garden theatre

In 1929 came the first hint of how Chelsea would develop, with a dazzlingly theatrical triptych of gardens from California, representing a redwood grove, Death Valley and the Mojave Desert. In fact, many aspects of present-day Chelsea were already familiar in the 1930s.

Judges deliberated and royalty admired before the show opened to the public. Overcrowding was already a problem, leading to timed tickets and reduced-price evening admission. Even the moans were similar – in 1931 the Daily Express was already calling for Chelsea gardens to be more down-to-earth.

When World War II broke out, the Flower Show was cancelled for the duration, but an austerity Chelsea was staged, with tremendous effort, in 1947. The Coronation in 1951 was celebrated, as in 1937, with an extravaganza of plants from around the Commonwealth. By the 1960s, rock gardens had fallen from fashion, and the nurserymen who had dominated the show were about to give way to a new elite, garden designers.

In the years that have followed, Chelsea has continued to hold a mirror up to our gardening preoccupations. The 1960s espoused gardening for the masses. The first garden for the disabled appeared in 1967; wildlife gardens became increasingly popular from the late 1980s; the 1990s were all about lifestyle and design.

In recent years, Chelsea has taken up ecological and social concerns – banning limestone, peat and rainforest timber, and encouraging children, prisoners and community gardeners to show their skills. In recent years, olive and oak trees have been banned thanks to plant disease concerns.

Royals, rather than just visiting the show, have become actively involved – Prince Harry collaborated with Jinny Blom on the Garden for Lesotho in 2013, while the Duchess of Cambridge worked with the RHS on their Back to Nature garden in 2019.

Chelsea has always been strong on nostalgia. But every few years comes a garden that breaks the mould – Christopher Bradley-Hole’s minimalist Latin Garden in 1997, or the haunting DMZ Forbidden Garden in 2012, that proved that even show gardens can have seriousness and meaning.

In 2020 the show went virtual during the pandemic and 2021’s September show, with a focus on autumn plants, was a welcome diversion from the norm. In 2022, the show is back to its usual May slot, taking place from the 24-28 May 2022. It has a new sponsor, The Newt in Somerset.

The RHS recently launched its Sustainability Strategy, which saw the organisation shifting from a gardening charity to one with more of an environmental focus, and we can expect to see this increasingly reflected at Chelsea.

This year, native plants that benefit wildlife are predicted to take centre stage, and the RHS says we can expect to see blossoming hedgerows, native trees including hawthorn, hazel, crab apple, hornbeam and sweet chestnut, wildflowers like cow parsley and poppies, swathes of wildflower meadows and ‘weeds’ such as nettles. The RHS has noticed that many designers are using a calming pastel colour palette of white, cream, green and pink, and lots of naturalistic planting.

First-time designers Lulu Urquhart and Adam Hunt are using native British plants to create a naturally rewilded landscape following the reintroduction of beavers in south-west England in their A Rewilded Britain garden, while Sarah Eberle’s Medite Smartply Building the Future Garden promises to be another naturalistic design using rare, damp-loving and wild plants and sustainable materials.

The Meta Garden: Growing the Future will focus on the connection between plants and fungi in our woodland ecosystems and Juliet Sargeant’s Blue Peter Garden will focus on the role of soil in mitigating the effects of climate change.

Mental health and wellbeing are also big themes for 2022. Chelsea veteran Andy Sturgeon will be creating a sanctuary for conversation on Main Avenue for his chosen charity, Mind. A circular seating area set within curved walls will be a place to sit side by side, surrounded by meadow-like spaces and birch trees. A gravel path will lead to a lower level, bringing people together before the garden opens out before them.

The smaller Sanctuary Gardens will also reflect the healing power and serenity of nature. Kate Gould’s ‘Out of the Shadows’ garden, for example, will be a contemporary spa space, complete with swim spa, climbing bars, yoga, meditation and relaxation areas and lush, tropical planting.

This year, the Great Pavilion, home to exhibits from some of the country’s best nurseries and growers, will also be home to a garden design category called All About Plants. Four first-time designers under 40 will show how gardening and greenery can influence our mental and physical health, each garden celebrating the work of a charity.

The 2022 show will also cater for a younger, more urban audience, with balcony and container garden categories continuing from last year. After a popular debut in 2021, the Houseplant Studios will also return, giving stylists an opportunity to style a room of a house.

No less than twelve gardens are being created for charities, thanks to an initiative called Project Giving Back. In 2022, 2023 and 2024, this grant-making scheme will provide funding for 42 gardens for good causes. Andy Sturgeon’s Mind garden, as well as Chris Beardshaw’s garden for the RNLI and Juliet Sargeant’s Blue Peter garden are just three of the gardens being funded this way this year. It’s hoped that all 12 gardens will have permanent homes with their charities after the show.

Helena Pettit, RHS Director of Gardens & Shows, says: “We can’t wait to see the return of a spring RHS Chelsea Flower Show in 2022 and welcome our visitors back after a two-year wait.” We can’t wait either.

For more information and to book tickets, visit www.rhs.org.uk/chelsea

Sign up to our Chelsea newsletter to stay up to speed with the upcoming Chelsea Flower Show.

Authors

Veronica Peerless is a trained horticulturalist and garden designer.

Niwaki bundle worth £57 when you subscribe

Subscribe to Gardens Illustrated magazine and claim your Niwaki bundle worth £57

*UK only

Container Gardening Special Edition

The Gardens Illustrated Guide to Container Gardening.

In this special edition, discover colourful flower combinations and seasonal planting schemes for pots designed by leading plantspeople, and essential know-how for container gardening success. Just £9.99 inc UK p&pBy entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Gardens of the Globe

From botanical wonders in Australia to tranquil havens closer to home in Ireland, let this guide help you to discover some of the most glorious gardens around the world

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.