What is a Japanese Garden?

Finely tuned and rich in detail, Japanese gardens invite us to engage with nature, and have much to teach us about the aesthetics of design and the appreciation of beauty. Words Andy Sturgeon

There are certain things – ouzo and retsina are two good examples – that should never be taken out of their home country. This is true for Japanese gardens. Make one outside of Japan and it is often little more than a Disneyfied pastiche. The reasons are simple: Japanese gardens are a complex art form based on deep meanings and symbolism and are closely bound to that country’s spiritual culture and environment.

Yet if you can distil the essence of what they are, there are so many aesthetic principles to be learned and that can be applied to the design of Western gardens. Fundamentally, Japanese gardens are a convergence of architecture, gardens and environment. And that link to the environment, both physically and metaphorically, seems particularly poignant at this moment in time. Japanese gardens have also always been considered to have the power to promote a healthy, spiritual life, something we’ve only recently grasped in the West.

Stone gardens are perhaps the most famed style. This is a representational world full of symbolism where rocks and seas of gravel may replicate an actual landscape or something as intangible as longevity. Trees and waterfalls are considered to emit a spiritual aura and were once deified; an entire thought process that is quite alien to us. There are lessons here. A single, immovable rock brings a stillness and therefore tranquillity. There may be a few well-placed objects surrounded by lots of space in a perfect balance of mass and void and there is always a comfortable flow connecting those empty spaces. Manipulation of perspective creates the illusion of a larger plot. Large rocks in the foreground lead to much smaller ones behind and vertical accents, such as trees, enforce the effect.

Japanese gardens are often referred to as sanctuaries and this is in part a reflection of the importance of enclosure, which is usually the starting point as a space is framed with buildings and fences. The threshold is important too so that the visitor can experience a ‘purifying sensation’ as they step from one contrasting environment into another. We can achieve this transition with a gate or even by squeezing between two hedges. But the garden inside must then be peaceful, balanced, unhurried and harmonious.

Significantly Japanese gardens are timeless, thanks to the use of natural materials and plants, and because even contemporary designs are so heavily inspired by ancient landscapes and nature itself. There is always a dialogue between the existing site and the new garden and this may come from respecting the existing topography or by echoing materials already present. There is always a beauty in the materials themselves.

Our own gardening culture has been about borrowing from nature, then controlling it and turning it into something else. Japanese gardens are simply a reimagining of nature itself. So while European gardens may be formal, symmetrical and sometimes static, Japanese gardens favour asymmetry as this imbalance brings an energy and dynamism to the garden. Low-level topiary in organic forms is used rather than grand individual statements, totems and rectangles, and these rounded, clipped shapes are often flowing, creating movement and relating to each other. Although they may be obviously clipped and contrived, they make a profound link with the natural scenery beyond. Borrowed views, known in Japanese as shakkei, are often used.

The blurring of inside and out is old hat to the Japanese. Their buildings with sliding shoji doors and paper panels were invented to blend architecture and nature. But where we in the West go wrong is that we consider these sorts of devices as a way to get to the outside dining table or lounge seat more easily when instead we should think of this as a way to bring nature and landscape right up to the house to rub against our souls.

Often the Japanese compose a view like a stage set or painting to be experienced from a fixed vantage point. In a courtyard garden, or naka-niwa, the small size puts an incredible emphasis on the placement of objects within which could be carefully chosen rocks and moss and perhaps a slender tree that encourages you to look up to the sky and appreciate the sense of openness, which can be vital in a tiny space.

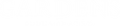

Stroll gardens are different. These are larger gardens and are never seen in their entirety from any single point. Boundaries are hidden and they unfold themselves as winding paths and stepping stones that force visitors to focus on specific vistas. Concealed surprises are at first revealed and then withdrawn as the paths lead on. Walking in the shadows beneath overhanging trees might lead to a bright, sunlit clearing. A narrow threshold unexpectedly delivers you to a wide-open space. These contrasting events are all designed to enrich the journey and bring the garden to life.

Andy Sturgeon is an internationally renowned landscape and garden designer. He is the winner of eight Gold medals at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show, including Best in Show in 2019. andysturgeon.com

Niwaki bundle worth £57 when you subscribe

Subscribe to Gardens Illustrated magazine and claim your Niwaki bundle worth £57

*UK only

Container Gardening Special Edition

The Gardens Illustrated Guide to Container Gardening.

In this special edition, discover colourful flower combinations and seasonal planting schemes for pots designed by leading plantspeople, and essential know-how for container gardening success. Just £9.99 inc UK p&pBy entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Gardens of the Globe

From botanical wonders in Australia to tranquil havens closer to home in Ireland, let this guide help you to discover some of the most glorious gardens around the world

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.